By Femi Mimiko

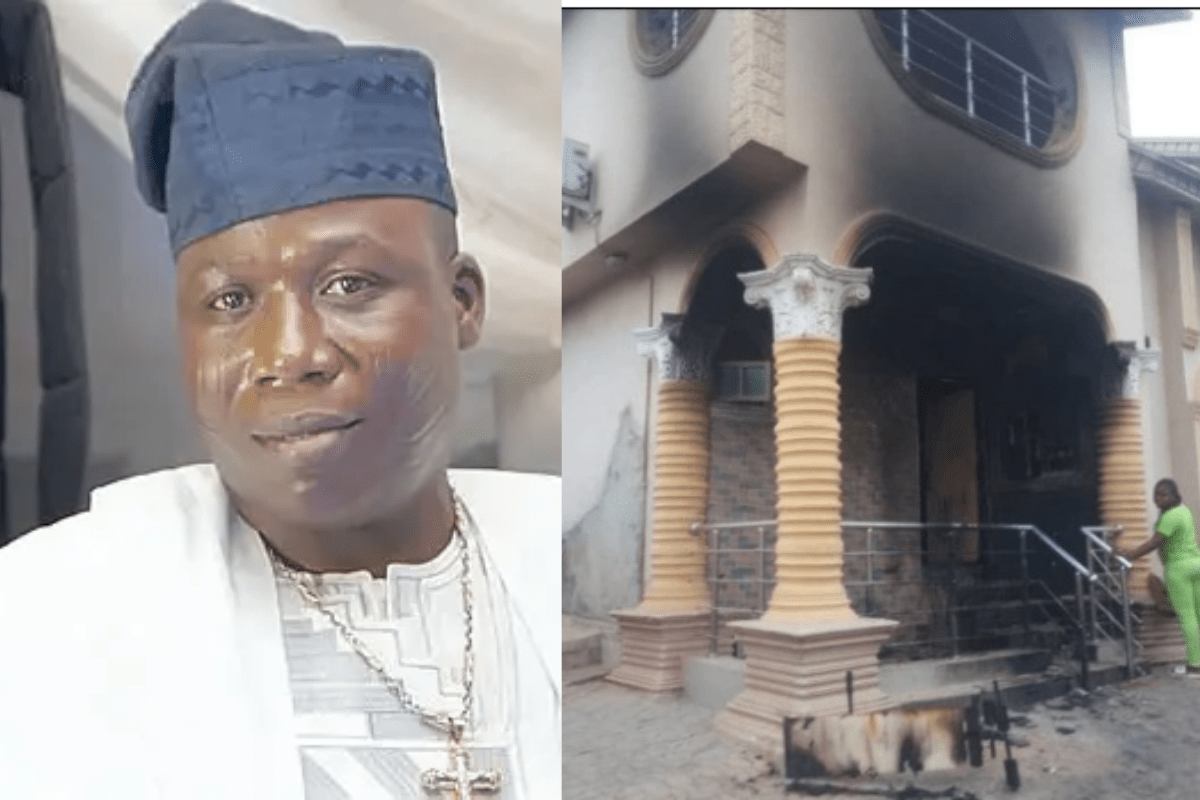

I read the press statement put out by DSS on its early morning invasion of Sunday Igboho’s abode and couldn’t stop wondering what was happening! How could a surprise armed attack by an agency of the State, on a man’s premises, and without a search warrant, constitute the appropriate response to his rascality?

How many hideouts of bandits and sundry highly disruptive elements wreaking havoc and making a boast of slaughtering soldiers has the DSS stormed in similar manner? Aren’t we aware that some State governments sit at negotiating tables with unrepentant killer herdsmen? Didn’t we read about one governor who gave the impression he had to pay some murderers to persuade them to stop killing innocent citizens in his state?

By the way, aren’t we aware that it was the widespread frustration with the lackadaisical attitude of the police to reports of murder, kidnapping, rape, and wanton violation of regular peoples in the Southwest that threw up Igboho? How is his arrest, or indeed possible murder, going to be a solution to the problem? I read a well-appointed piece by a professor who, in self-same manner, is asking how Igboho’s neutralisation would put an end to banditry in the Northwest, including kidnapping of hapless students in Kaduna State. These are fundamental issues we should address, not Igboho as a person, or his more worrisome acts and rhetoric.

Look at the Nnamdi Kanu (IPOB) guy, who singlehandedly locked down the entire Southeast, multiple times. Smartness dictates that such a person, regardless of the level of irritation he may represent, be handled with utmost caution; otherwise, you have more problems created than you set out to solve.

I think the country should be more focused on the fundamentals of the challenge our nation faces, and the objective manner in which enduring solutions can be found. It’s been established, by the way, that all of the wars fought in the last century – from the first World War, through those attendant upon the Arab-Israeli conflict, to the ones on the Indian subcontinent – were consequent upon miscalculation on the part of political leaders (Stoessinger, 2011). We must be concerned that our leaders don’t push us into similar situations through wrong decisions and precipitate acts. This is what patriotism, to my mind, suggests, not superficial handling of very serious nation-building challenges.

We don’t want our own nation to disintegrate; because, obviously, we are all better together. And of course, war at this time doesn’t make any sense at all. This is the overarching objective. The way to go about that is to ensure we act right by making our system more inclusive. You don’t solve a problem by neglecting it. That was the mistake the communist leaders, who created and nurtured the USSR for more than 70 years, made. It was the error President Josip Broz Tito made for more than four decades in Yugoslavia. These things are not rocket science; and we all have a duty to get government to listen to these pieces of advice, deriving their substance from the lessons of history.

We saw the futility of extant approach in relation to how the Nigerian State handled Muhammed Yusuf, and we got thoroughly messed up! We lost control of an ordinarily benign conflict and got ‘rewarded’ with Boko Haram, and, according to UNDP’s most recent statistics, 350,000 deaths – and still counting! Why are we going that same route again – with Kanu, with Igboho, with el-Zakzaky? Why?

To his credit, President Umaru Yar’Adua applied greater wisdom, born of genuine self-confidence, to the Niger Delta conundrum, and snatched relative peace from the jaws of war. His Amnesty programme may not be perfect, but it was good enough to return Nigeria’s economy to the path of stability. It is concerning those fresh threats, and ultimatum are oozing out of the region again!

Meanwhile, those who assume that victory for whichever looks like the larger army is a forgone conclusion, should find out why army generals are usually the last to root for war. It’s because they know. For 40 years, the Ethiopian military could not suppress Eritrean agitation. The latter broke away. East Timor couldn’t be stopped by Indonesia’s formidable military. It became a new nation. The late John Garang fought Sudan for more than half a century until the South Sudan republic of his dream became a reality. The US military, the most formidable in the world, is now scurrying out of Afghanistan; not because the job (whatever it is) has been done, but precisely because it is not doable! I wrote repeatedly a few months ago urging Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed of Ethiopia to negotiate with Tigray rather than go to war. The counsel obviously didn’t cut an ice with the Nobel Peace Laureate. He chose the path of war. His military swiftly moved into and occupied Tigray’s capital, and overwhelmed the province. Now, less than a year later, keen observers are acknowledging that the tide of war is turning, and Addis Ababa is beating a hurried retreat through a unilateral declaration of ceasefire that the ‘rebels’ are regarding with utter disdain! Why do we need to open our eyes and allow Nigeria that has all the potentials of being one of the greatest countries on earth fall into these types of nonsensical situations?

I say, for the umpteenth time, that the solution to all of these is to evolve a more inclusive system, where everyone feels they have a stake. Arrests, armed storming of private residences, vitriolic press statements, and tough talk on television, don’t solve the type of problems we are confronted with today. Not even the expansion of infrastructure; not a seemingly powerful line-up of political gladiators on one side is good enough to contain this commitment to secession that is fast taking a life of its own across the land. The work of the ‘hidden persuaders’ robust as it may seem, won’t help in this instance.

Please, make no mistake about it; self-determination is not an unlawful act. As a concept, it basically speaks to the desire of a culturally distinct people for greater control of their own affairs, within an existing political structure. It is conceptually different from secession, which is about forceful, often acrimonious, and rancorous break away from a hitherto composite structure. The most effective way of dousing the growing fire of secession in the land is to allow a greater degree of regional autonomy (self-determination), such that can make for autochthonous development, while stanching and ultimately putting out the clamour for secession. What is required, therefore, is to do away with the basis of alienation and estrangement, as felt by individuals, regional, ethnic, religious or indeed ideological constituencies. These, I presume, should be our concern, not mere verbal objection to break-up of the nation, which doesn’t really amount to much.

Femi Mimiko, mni can be reached via femi.mimiko@gmail.com he first published the opinion on July 3, 2021.